What Part of Speech Is Again

In traditional grammer, a part of speech or function-of-spoken language (abbreviated equally POS or PoS) is a category of words (or, more by and large, of lexical items) that accept like grammatical backdrop. Words that are assigned to the aforementioned lexical category generally display similar syntaxic behavior (they play similar roles within the grammatical structure of sentences), sometimes similar morphology in that they undergo inflection for similar backdrop and even similar semantic behavior.

Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, or determiner. Other Indo-European languages besides have substantially all these word classes;[ane] 1 exception to this generalization is that Latin, Sanskrit and most Slavic languages do not have articles. Beyond the Indo-European family, such other European languages as Hungarian and Finnish, both of which belong to the Uralic family, completely lack prepositions or accept only very few of them; rather, they have postpositions.

Other terms than office of speech—particularly in mod linguistic classifications, which oftentimes brand more precise distinctions than the traditional scheme does—include word grade, lexical class, and lexical category. Some authors restrict the term lexical category to refer merely to a particular type of syntactic category; for them the term excludes those parts of speech that are considered to be functional, such as pronouns. The term form class is too used, although this has diverse conflicting definitions.[2] Word classes may be classified as open or airtight: open up classes (typically including nouns, verbs and adjectives) acquire new members constantly, while closed classes (such as pronouns and conjunctions) learn new members infrequently, if at all.

Almost all languages accept the give-and-take classes substantive and verb, but across these 2 in that location are pregnant variations among unlike languages.[three] For case:

- Japanese has every bit many as three classes of adjectives, where English has one.

- Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese have a grade of nominal classifiers.

- Many languages practice not distinguish between adjectives and adverbs, or betwixt adjectives and verbs (see stative verb).

Considering of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, assay of parts of spoken communication must be done for each private language. Nevertheless, the labels for each category are assigned on the footing of universal criteria.[3]

History [edit]

The nomenclature of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.[four]

Bharat [edit]

In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four master categories of words:[v]

- नाम nāma – noun (including adjective)

- आख्यात ākhyāta – verb

- उपसर्ग upasarga – pre-verb or prefix

- निपात nipāta – particle, invariant word (perhaps preposition)

These iv were grouped into 2 larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

The ancient work on the grammer of the Tamil language, Tolkāppiyam, argued to take been written effectually two,500 years ago, classifies Tamil words equally peyar (பெயர்; noun), vinai (வினை; verb), idai (part of speech which modifies the relationships between verbs and nouns), and uri (word that further qualifies a noun or verb).[6]

Western tradition [edit]

A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialog, "sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]".[7] Aristotle added another class, "conjunction" [sýndesmos], which included not only the words known today as conjunctions, simply also other parts (the interpretations differ; in one interpretation it is pronouns, prepositions, and the article).[8]

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into 8 categories, seen in the Art of Grammer, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[9]

- Substantive (ónoma): a part of spoken communication inflected for example, signifying a concrete or abstract entity

- Verb (rhêma): a part of speech without instance inflection, simply inflected for tense, person and number, signifying an activeness or process performed or undergone

- Participle (metokhḗ): a part of speech sharing features of the verb and the substantive

- Commodity (árthron): a declinable part of oral communication, taken to include the definite article, but besides the basic relative pronoun

- Pronoun (antōnymíā): a role of speech substitutable for a substantive and marked for a person

- Preposition (próthesis): a lexical category placed earlier other words in composition and in syntax

- Adverb (epírrhēma): a lexical category without inflection, in modification of or in improver to a verb, adjective, clause, sentence, or other adverb

- Conjunction (sýndesmos): a part of speech bounden together the discourse and filling gaps in its interpretation

It can be seen that these parts of spoken language are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

The Latin grammarian Priscian (fl. 500 CE) modified the above eightfold system, excluding "commodity" (since the Latin language, different Greek, does not accept manufactures) but adding "interjection".[10] [xi]

The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding mod English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio. The category nomen included substantives (nomen substantivum, corresponding to what are today called nouns in English), adjectives (nomen adjectivum) and numerals (nomen numerale). This is reflected in the older English terminology noun substantive, substantive adjective and substantive numeral. Later[12] the adjective became a separate class, as often did the numerals, and the English give-and-take noun came to be applied to substantives merely.

Works of English grammar by and large follow the pattern of the European tradition every bit described above, except that participles are now unremarkably regarded as forms of verbs rather than as a split up part of speech communication, and numerals are frequently conflated with other parts of speech: nouns (cardinal numerals, e.g., "one", and collective numerals, e.one thousand., "dozen"), adjectives (ordinal numerals, due east.g., "start", and multiplier numerals, e.1000., "single") and adverbs (multiplicative numerals, e.g., "once", and distributive numerals, e.thousand., "singly"). 8 or nine parts of speech are commonly listed:

- substantive

- verb

- adjective

- adverb

- pronoun

- preposition

- conjunction

- interjection

- article or (more than recently) determiner

Some modernistic classifications define farther classes in improver to these. For discussion see the sections below.

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in well-nigh dictionaries:

- Substantive (names)

- a word or lexical detail cogent whatsoever abstract (abstruse noun: e.g. dwelling) or concrete entity (concrete noun: e.g. firm); a person (police officer, Michael), place (coastline, London), thing (necktie, television receiver), idea (happiness), or quality (bravery). Nouns can also be classified every bit count nouns or non-count nouns; some can belong to either category. The well-nigh common part of speech; they are called naming words.

- Pronoun (replaces or places over again)

- a substitute for a noun or noun phrase (them, he). Pronouns brand sentences shorter and clearer since they supplant nouns.

- Adjective (describes, limits)

- a modifier of a substantive or pronoun (large, brave). Adjectives make the pregnant of some other give-and-take (noun) more than precise.

- Verb (states action or being)

- a word denoting an action (walk), occurrence (happen), or state of beingness (exist). Without a verb a grouping of words cannot be a clause or judgement.

- Adverb (describes, limits)

- a modifier of an adjective, verb, or another adverb (very, quite). Adverbs make language more precise.

- Preposition (relates)

- a give-and-take that relates words to each other in a phrase or sentence and aids in syntactic context (in, of). Prepositions show the relationship between a noun or a pronoun with another discussion in the judgement.

- Conjunction (connects)

- a syntactic connector; links words, phrases, or clauses (and, simply). Conjunctions connect words or group of words

- Interjection (expresses feelings and emotions)

- an emotional greeting or assertion (Huzzah, Alas). Interjections express strong feelings and emotions.

- Article (describes, limits)

- a grammatical marker of definiteness (the) or indefiniteness (a, an). The article is not e'er listed among the parts of spoken language. It is considered by some grammarians to exist a type of adjective[13] or sometimes the term 'determiner' (a broader form) is used.

English words are not more often than not marked equally belonging to one role of speech or some other; this contrasts with many other European languages, which utilise inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can ofttimes be identified as belonging to a item function of speech and having sure additional grammatical backdrop. In English language, almost words are uninflected, while the inflected endings that be are generally ambiguous: -ed may mark a verbal by tense, a participle or a fully adjectival form; -s may marker a plural noun, a possessive noun, or a present-tense verb form; -ing may marker a participle, gerund, or pure adjective or noun. Although -ly is a frequent adverb marker, some adverbs (e.g. tomorrow, fast, very) do not have that catastrophe, while many adjectives do accept it (east.g. friendly, ugly, lovely), as do occasional words in other parts of speech (e.thousand. jelly, fly, rely).

Many English words can belong to more one lexical category. Words like neigh, pause, outlaw, laser, microwave, and telephone might all be either verbs or nouns. In certain circumstances, fifty-fifty words with primarily grammatical functions can be used as verbs or nouns, as in, "We must await to the hows and not simply the whys." The procedure whereby a word comes to exist used as a dissimilar lexical category is called conversion or zero derivation.

Functional classification [edit]

Linguists recognize that the higher up list of eight or nine word classes is drastically simplified.[14] For instance, "adverb" is to some extent a catch-all class that includes words with many different functions. Some have fifty-fifty argued that the most bones of category distinctions, that of nouns and verbs, is unfounded,[15] or not applicable to certain languages.[16] [17] Modern linguists have proposed many dissimilar schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Common lexical category set divers by function may include the following (not all of them will necessarily be applicable in a given language):

- Categories that will usually be open classes:

- adjectives

- adverbs

- nouns

- verbs (except auxiliary verbs)

- interjections

- Categories that volition commonly be airtight classes:

- auxiliary verbs

- clitics

- coverbs

- conjunctions

- determiners (articles, quantifiers, demonstrative adjectives, and possessive adjectives)

- particles

- measure words or classifiers

- adpositions (prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions)

- preverbs

- pronouns

- contractions

- cardinal numbers

Inside a given category, subgroups of words may be identified based on more than precise grammatical backdrop. For example, verbs may be specified according to the number and type of objects or other complements which they take. This is called subcategorization.

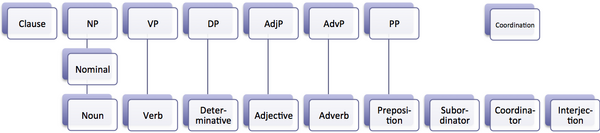

Many mod descriptions of grammer include non only lexical categories or word classes, but also phrasal categories, used to classify phrases, in the sense of groups of words that form units having specific grammatical functions. Phrasal categories may include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP) and and then on. Lexical and phrasal categories together are called syntactic categories.

Open and closed classes [edit]

Discussion classes may be either open or closed. An open class is ane that commonly accepts the addition of new words, while a closed class is ane to which new items are very rarely added. Open classes ordinarily comprise large numbers of words, while closed classes are much smaller. Typical open up classes constitute in English language and many other languages are nouns, verbs (excluding auxiliary verbs, if these are regarded as a separate class), adjectives, adverbs and interjections. Ideophones are often an open up class, though less familiar to English language speakers,[18] [19] [a] and are oftentimes open up to nonce words. Typical closed classes are prepositions (or postpositions), determiners, conjunctions, and pronouns.[21]

The open–airtight stardom is related to the stardom between lexical and functional categories, and to that betwixt content words and function words, and some authors consider these identical, but the connection is not strict. Open classes are by and large lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[22] while airtight classes are ordinarily functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions. This is not universal: in many languages verbs and adjectives[23] [24] [25] are closed classes, normally consisting of few members, and in Japanese the formation of new pronouns from existing nouns is relatively common, though to what extent these grade a distinct word class is debated.

Words are added to open classes through such processes as compounding, derivation, coining, and borrowing. When a new word is added through some such process, it can subsequently be used grammatically in sentences in the same means as other words in its class.[26] A closed grade may obtain new items through these same processes, but such changes are much rarer and take much more time. A closed class is normally seen every bit part of the core linguistic communication and is not expected to change. In English, for instance, new nouns, verbs, etc. are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to exist used in a unlike office of speech communication). However, it is very unusual for a new pronoun, for example, to get accepted in the language, even in cases where there may be felt to be a demand for one, as in the case of gender-neutral pronouns.

The open or closed status of word classes varies betwixt languages, even assuming that corresponding give-and-take classes exist. Nearly clearly, in many languages verbs and adjectives form closed classes of content words. An extreme example is found in Jingulu, which has only three verbs, while even the modern Indo-European Persian has no more than than a few hundred simple verbs, a nifty deal of which are archaic. (Some 20 Western farsi verbs are used as low-cal verbs to course compounds; this lack of lexical verbs is shared with other Iranian languages.) Japanese is similar, having few lexical verbs.[27] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of exact senses instead expressed periphrastically.

In Japanese, verbs and adjectives are closed classes,[28] though these are quite large, with near 700 adjectives,[29] [30] and verbs have opened slightly in contempo years. Japanese adjectives are closely related to verbs (they can predicate a judgement, for example). New verbal meanings are nearly always expressed periphrastically by appending suru ( する , to do) to a substantive, as in undō suru ( 運動する , to (practise) practice), and new adjectival meanings are nearly always expressed by adjectival nouns, using the suffix -na ( 〜な ) when an adjectival substantive modifies a substantive phrase, as in hen-na ojisan ( 変なおじさん , foreign homo). The closedness of verbs has weakened in recent years, and in a few cases new verbs are created by appending -ru ( 〜る ) to a noun or using information technology to replace the end of a word. This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the well-nigh well-established instance existence sabo-ru ( サボる , cut grade; play hooky), from sabotāju ( サボタージュ , sabotage).[31] This recent innovation aside, the huge contribution of Sino-Japanese vocabulary was nearly entirely borrowed equally nouns (often verbal nouns or adjectival nouns). Other languages where adjectives are closed course include Swahili,[25] Bemba, and Luganda.

By contrast, Japanese pronouns are an open form and nouns become used as pronouns with some frequency; a recent instance is jibun ( 自分 , self), now used by some immature men every bit a first-person pronoun. The status of Japanese pronouns as a distinct course is disputed,[ by whom? ] however, with some because information technology simply a use of nouns, not a distinct class. The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of accost vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.[32]

Some give-and-take classes are universally closed, nonetheless, including demonstratives and interrogative words.[32]

Come across too [edit]

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Sliding window based part-of-oral communication tagging

Notes [edit]

- ^ Ideophones exercise non always course a unmarried grammatical word class, and their nomenclature varies between languages, sometimes existence split up across other word classes. Rather, they are a phonosemantic word grade, based on derivation, just may be considered part of the category of "expressives",[18] which thus frequently form an open class due to the productivity of ideophones. Further, "[i]n the vast majority of cases, notwithstanding, ideophones perform an adverbial function and are closely linked with verbs."[20]

References [edit]

- ^ "A Grammer of Modern Indo-European, Part 3.ane first line of ??".

- ^ John Lyons, Semantics, CUP 1977, p. 424.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Paul (2005). Analyzing Grammar: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN978-0-521-01653-7.

- ^ Robins RH (1989). Full general Linguistics (4th ed.). London: Longman.

- ^ Bimal Krishna Matilal (1990). The word and the earth: Bharat's contribution to the study of language (Chapter 3).

- ^ Ilakkuvanar South (1994). Tholkappiyam in English with critical studies (2nd ed.). Educational Publisher.

- ^ Cratylus 431b

- ^ The Rhetoric, Poetic and Nicomachean Ideals of Aristotle, translated by Thomas Taylor, London 1811, p. 179.

- ^ Dionysius Thrax. τέχνη γραμματική (Art of Grammar), ια´ περὶ λέξεως (xi. On the word):

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

λόγος δέ ἐστι πεζῆς λέξεως σύνθεσις διάνοιαν αὐτοτελῆ δηλοῦσα.

τοῦ δὲ λόγου μέρη ἐστὶν ὀκτώ· ὄνομα, ῥῆμα,

μετοχή, ἄρθρον, ἀντωνυμία, πρόθεσις, ἐπίρρημα, σύνδεσμος. ἡ γὰρ προσηγορία ὡς εἶδος τῶι ὀνόματι ὑποβέβληται. - A give-and-take is the smallest part of organized speech.

Speech is the putting together of an ordinary word to express a consummate thought.

The form of word consists of eight categories: noun, verb,

participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb, conjunction. A common noun in class is classified as a noun.

- λέξις ἐστὶ μέρος ἐλάχιστον τοῦ κατὰ σύνταξιν λόγου.

- ^ [penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Quintilian/Institutio_Oratoria/1B*.html This translation of Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria reads: "Our own language (Notation: i.e. Latin) dispenses with the articles (Note: Latin doesn't have manufactures), which are therefore distributed among the other parts of speech. But interjections must exist added to those already mentioned."]

- ^ "Quintilian: Institutio Oratoria I".

- ^ Run into for example Beauzée, Nicolas, Grammaire générale, ou exposition raisonnée des éléments nécessaires du langage (Paris, 1767), and earlier Jakob Redinger, Comeniana Grammatica Primae Classi Franckenthalensis Latinae Scholae destinata ... (1659, in German and Latin).

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar by Bas Aarts, Sylvia Chalker & Edmund Weine. OUP Oxford 2014. Page 35.

- ^ Zwicky, Arnold (30 March 2006). "What function of speech is "the"". Language Log . Retrieved 26 Dec 2009.

...the school tradition well-nigh parts of voice communication is so desperately impoverished

- ^ Hopper, P; Thompson, S (1985). "The Iconicity of the Universal Categories 'Noun' and 'Verbs'". In John Haiman (ed.). Typological Studies in Language: Iconicity and Syntax. Vol. 6. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Visitor. pp. 151–183.

- ^ Launey, Michel (1994). Une grammaire omniprédicative: essai sur la morphosyntaxe du nahuatl classique. Paris: CNRS Editions.

- ^ Broschart, Jürgen (1997). "Why Tongan does it differently: Categorial Distinctions in a Language without Nouns and Verbs". Linguistic Typology. 1 (2): 123–165. doi:10.1515/lity.1997.1.2.123. S2CID 121039930.

- ^ a b The Art of Grammer: A Applied Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 99

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, "African ideophones", in Audio Symbolism, p. 179

- ^ G. Tucker Childs, "African ideophones", in Audio Symbolism, p. 181

- ^ "Sample Entry: Part Words / Encyclopedia of Linguistics".

- ^ Carnie, Andrew (2012). Syntax: A Generative Introduction. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–52. ISBN978-0-470-65531-iii.

- ^ Dixon, Robert Thousand. W. (1977). "Where Accept all the Adjectives Gone?". Studies in Language. 1: nineteen–80. doi:10.1075/sl.i.1.04dix.

- ^ Adjective classes: a cross-linguistic typology, Robert M. Due west. Dixon, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, OUP Oxford, 2006

- ^ a b The Fine art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 97

- ^ Hoff, Erika (2014). Linguistic communication Evolution. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning. p. 171. ISBN978-1-133-93909-2.

- ^ Categorial Features: A Generative Theory of Word Course Categories, "p. 54".

- ^ Dixon 1977, p. 48.

- ^ The Typology of Adjectival Predication, Harrie Wetzer, p. 311

- ^ The Fine art of Grammer: A Applied Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 96

- ^ Adam (2011-07-eighteen). "Homage to る(ru), The Magical Verbifier". ;

- ^ a b The Art of Grammar: A Practical Guide, Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, p. 98

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Parts of speech at Wikimedia Commons - The parts of voice communication

- Guide to Grammar and Writing

- Martin Haspelmath. 2001. "Discussion Classes and Parts of Speech." In: Baltes, Paul B. & Smelser, Neil J. (eds.) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Pergamon, 16538–16545. (PDF)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Part_of_speech

0 Response to "What Part of Speech Is Again"

Post a Comment